I.

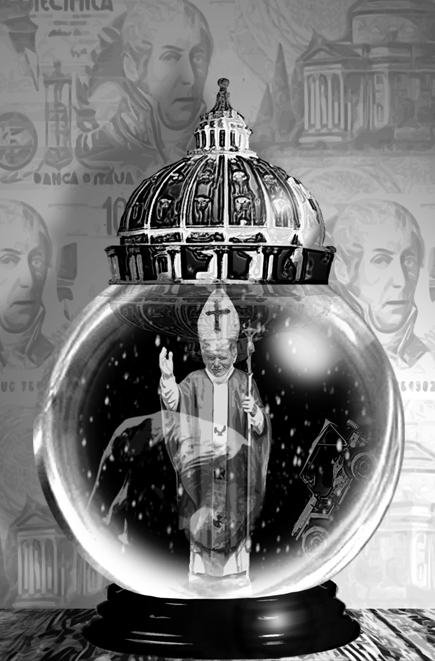

When Christ had driven the money-changers

out of the temple, he couldn’t foresee

the irony— two thousand years later,

I’m outside of the Vatican City

haggling over a Pope in a snow dome

as my wife digs for Lire in her purse.

There is a perverse energy to Rome,

especially inside St. Peter’s Church

where saints and martyrs vie for attention

in the tapestries, frescoes, and friezes—

even the Pieta near the entrance

eroticizes Mary and Jesus,

with their smooth bodies in blissful repose

like lovers having a post-coital smoke.

II.

Joah points to a handsome youth and swoons:

“I could see him in an underwear ad.”

For the remainder of the afternoon

I imagine the slight Italian man

in boxer briefs, tensing for a camera.

In the evening, we take our gracious hosts

to watch “Wozzeck,” a German opera,

then make our way backstage after the show

by posing as American pop stars.

Zubin Mehta fields reporter’s questions

while the lead actor drinks bottled water

and blots his armpits with a wet napkin.

“Do you speak English?” I ask in German.

“Bloody well should.” he quips. “I’m from England.”

III.

On the train back to Florence, my wife rests

as the cypress trees outside the window

gradually recede into the mist

then fade altogether in the shadows.

I stare into the distance, eyes half-closed,

and remember the previous morning:

the frantic mothers running toward the Pope

when he entered the square in a white Jeep,

comically ascending the marble steps

like Ernest Hemingway on safari,

his arms shaking as he reached out to bless

the frightened children. Then I fall asleep

and dream of a woman in the desert

wandering in the sand with a hair shirt.

IV.

I’m jostled awake in the train station,

and immediately look for a pen

to commit the images to paper.

I dreamt of the Penitent Magdalene,

Donatello’s apocryphal figure

in the museum behind the Duomo

which I had visited the week before.

In every doorway, a guard was posted

reminding the tourists: “Please do not touch.”

Their words now took the shape of a poem—

a reference to Mary being rebuffed

after Jesus Christ crawled out of his tomb

and said to her “Noli Me Tangere”

when she threw herself at his wounded feet.

V.

I was uprooted by Donatello—

my trunk carved into a woman’s body,

bent in an eternal contrapposto,

and christened the Apocryphal Mary,

Thus my creator was finished with me

and placed me in a room with large sculptures

where I stood unmolested many years—

when at last, a great flood broke through the doors,

spilling high above the window ledges.

I floated quickly past the Bargello

and saw the bottoms of the old bridges

as I traveled down the turbid Arno

behind Cimabue’s yellow Jesus

and Ghiberti’s gold Gates of Paradise.